Meeting created at: 23rd Jan, 2026 - 6:29 PM1

Speaker 1: You are listening to Eye of the Triangle, WKNC's weekly public affairs program from the campus of North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

Speaker 1: Any views and opinions expressed during Eye of the Triangle do not represent NC State or student media.

Speaker 1: Hello, everyone.

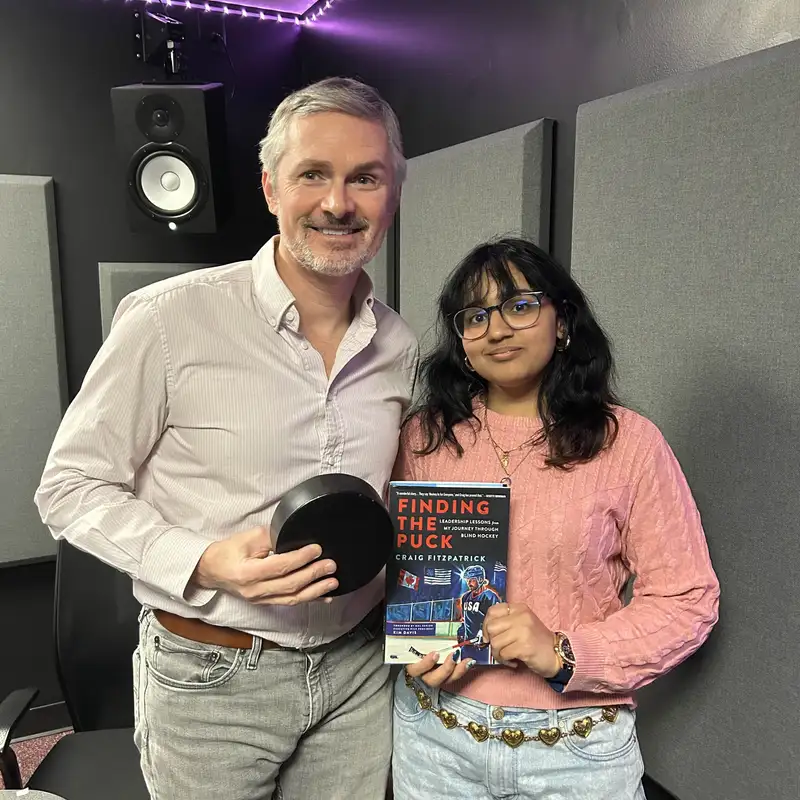

Speaker 1: This is Shradha Bhatia.

Speaker 1: I'm the public affairs director here at WKNC 88.1, and on today's episode, we're bringing you a conversation that sits at the interaction of sports resilience and disability advocacy.

Speaker 1: So I had the opportunity to speak with Craig Fitzpatrick, a blind hockey player, author, and advocate who's helping redefine what accessibility and inclusion in sports can look like.

Speaker 1: In this episode, we can talk about his journey into blind hockey, the challenges and the misconceptions surrounding disability in athletics, and how adaptive sports are creating space for people who are often overlooked.

Speaker 1: This conversation is more than just hockey.

Speaker 1: It's about independence, representation, and what it means to reclaim agency in spaces that weren't originally built with everyone in mind.

Speaker 1: So if you're interested in stories of resilience, inclusive sports, and how communities can do better when it comes to accessibility, you're in the right place.

Speaker 1: So here's my interview with Craig Fitzpatrick.

Speaker 1: Hey, Craig.

Speaker 1: Welcome to wknc.

Speaker 1: Thank you so much for having the time to chat with me.

Speaker 1: And today I'm really excited to hear your story, especially how hockey has played such a huge role in your life.

Speaker 1: So before all the TV appearances and the book, what did hockey mean to you growing up?

Speaker 2: Well, first of all, thanks for having me.

Speaker 2: I haven't been on a college campus in quite some time, so this is pretty cool for a guy like me.

Speaker 2: The question about what hockey meant to me leading up to the book coming out and some of the appearances that I've been doing lately, is really a story about someone finding a passion later in life and then turning that passion into fuel for the rest of your life.

Speaker 2: So for me, I saw my first hockey game when I was 19 or 20 years old as an undergrad at the Air Force Academy, but didn't get a chance to play until almost double that time in Life.

Speaker 2: I was 37 when I tried ice skating for the first time.

Speaker 2: So for those listening that might be a little younger than that, imagine if you were growing up in the Carolinas like I did.

Speaker 2: I'm from Irmo, South Carolina.

Speaker 2: And you kind of thought hockey was cool because you like the fighting and you like the hitting, but you didn't really know anything about what it would take to play.

Speaker 2: And then finding out later in life that playing a game like that might be possible for you.

Speaker 2: It really changed a lot of other things for me in my life.

Speaker 2: We'll dive into some of that in the interview.

Speaker 2: But really, in a nutshell, I would say that leading up to writing the book and while I was playing hockey, it was really turning a passion into a purpose.

Speaker 1: Oh, wow.

Speaker 1: So you say you went to the Air Force Academy.

Speaker 1: Do you feel like that experience helped you handle challenges like this?

Speaker 2: For sure.

Speaker 2: And for anyone that's in undergrad right now, or maybe going through a master's or a doctoral program, there are the challenges that come from the academics.

Speaker 2: And I know NC State's a really good school, so I'm sure the rigors of the academics here are their own challenge.

Speaker 2: But then there's also what you go through in life at that stage, at that age, and then figuring out how to manage yourself as a human being, figuring out how to balance, maybe choosing something that you might love to do and have an interest in or passion for with making money or with leveraging a social network.

Speaker 2: There.

Speaker 2: There are all these things that you've got to balance when you're going through an academic experience, like I had at the Air Force Academy.

Speaker 2: And at least I knew when I graduated I was going to have a job.

Speaker 2: I knew generally what I was going to be doing, right?

Speaker 2: It's going into the Air Force.

Speaker 2: So you raise your right hand and you say, yes, I promise to do this job when I graduate.

Speaker 2: That's maybe different than some of the experiences that the vast majority of the undergrads here have.

Speaker 2: Unless you're an rotc, right?

Speaker 2: Then you're in the same situation.

Speaker 2: You know what your job's going to be.

Speaker 2: So for me, I was figuring out who I was.

Speaker 2: At the same time I was figuring out what I had a talent for academically.

Speaker 2: At the same time I was figuring out how to make it through the other parts of going to a military academy that were hard.

Speaker 2: Things like having to study military arts and sciences, having to play a sport, having to balance a much longer list of things that you're supposed to do every day than you actually had time for and time management, all the same things that a lot of people go through in a college experience.

Speaker 2: Stack on top of that, the fact that I really didn't come from a family with a lot of structure.

Speaker 2: I was raised by a single mom and lost my dad to a heart attack when I was 10.

Speaker 2: The culture shock of going to a military school at the age of 17.

Speaker 2: I started a year early, and then adapting myself to that environment really got me ready for a lot of the other hard things that I was going to do later in life.

Speaker 2: Everybody has their own kind of hard, right?

Speaker 2: So if you.

Speaker 2: If you move away from home and you go to this place where the focus is supposed to be learning and the classroom is part of the learning, but then there's all these other sorts of learning that happen for you at that stage in life.

Speaker 2: It's its own kind of hard for everybody that does it.

Speaker 2: Right.

Speaker 2: And for me, adjusting to living away from home, adjusting to being told exactly what time to wake up every day, what to wear every day, those were their own kind of hard for a little bit.

Speaker 2: But then those things made life easier in some ways.

Speaker 2: Right.

Speaker 2: Like you probably woke up and picked out your clothes this morning.

Speaker 1: Right?

Speaker 1: Yeah.

Speaker 2: I didn't have to do that when I was in college, so.

Speaker 2: And I didn't.

Speaker 2: I didn't have to decide what I was going to have for lunch.

Speaker 2: That was decided for me.

Speaker 2: Right.

Speaker 2: So there are a lot of things about self management that if you go to a school with more of a military focus, you have to do a lot every day.

Speaker 2: But some of those things are sort of handed to you or told to you.

Speaker 2: And so there were things that were much harder about going to the Air Force Academy than a typical college experience.

Speaker 2: But some of the other things, in hindsight, I don't know what I would have done if I had to manage my own schedule all the time and figure out what I was going to eat and get myself dressed in.

Speaker 2: So the things that I took away from that were.

Speaker 2: First of all, I know that I can figure out how to prioritize a really long list of things I'm supposed to do every day into the things that I know I'm going to have time to do that day and then take care of the most important few things first and then figure out what else I have time left for.

Speaker 2: But that time management piece has become really core to who I am as a person.

Speaker 2: Just not like a skill that I have in the.

Speaker 2: In the workplace or in the way that I manage the rest of my life.

Speaker 1: Okay.

Speaker 1: And so I have a big question for you now.

Speaker 1: So, you know, when did you first notice your vision changing and how did that affect you, the way you played?

Speaker 2: Yeah, in hindsight, I probably should have noticed my vision changing before I noticed it.

Speaker 2: So for anyone that has studied any sort of neuroscience or maybe even biology, there's this concept called neuroplasticity, which means that Our brains are made up of a bunch of different parts that manage different functions for you.

Speaker 2: And the visual cortex is directly behind your optic nerves.

Speaker 2: And that part of your cerebellum is responsible for a lot of the processing that drives executive function.

Speaker 2: By providing the information that you need to make decisions and manage what you see and think about the little decisions that you make every day that involve vision, well, your brain can kind of ride the wave of losing a little bit of vision at a time and stay out ahead of that wave by adapting itself around the parts of your vision that you're losing before you even realize it.

Speaker 2: And in hindsight, that's what was happening to me maybe as.

Speaker 2: As early on as while I was in undergrad, certainly shortly after I graduated from college and while I was serving on active duty in the Air Force.

Speaker 2: I didn't consciously realize that I was losing my vision until it was far too late, until I was well past the state where I was legally blind.

Speaker 2: So I was deployed with the Air Force in the fall of 2000.

Speaker 2: During that deployment, there was lots of stress, aviation chemicals, no sleep.

Speaker 2: And these are all factors that create a ripe environment for.

Speaker 2: For your retinas to be completely washed out.

Speaker 2: So I have a condition called Stargardt's disease.

Speaker 2: And between having that underlying genetic condition and being exposed to the environment that I was in the fall of 2000 while I was deployed, it was the perfect storm.

Speaker 2: I came back from that deployment, and by the spring of 2001, I was already probably, at that point, passed legally blind, was waking up to the fact that might be the case.

Speaker 2: And then by the spring of 2002, I was well past legally blind, which is when the Air Force caught it during a routine eye exam and then began the process of medically discharging me once I was diagnosed with the condition that I have, which is called Stargardt's disease.

Speaker 1: So when you found out that you have that genetic disease.

Speaker 1: So did you ever think that maybe hockey isn't for you?

Speaker 2: Well, I didn't know yet.

Speaker 2: So I became a hockey fan in the mid-90s, and my vision was normal then.

Speaker 2: I could see the first game that I went to.

Speaker 2: But I didn't start ice skating until I was 37 years old.

Speaker 2: So I have to look back on that time when I was diagnosed and think of a long list of things that I thought might not be for me.

Speaker 2: There were things that I was being told I couldn't do anymore.

Speaker 2: I found out pretty quickly that I was going to lose my driver's license.

Speaker 2: And for anyone that's listening to this that is going through vision loss or some sort of other major thing that you're having taken away from you, like being able to drive or being able to recognize your mother's face at any distance in an airport.

Speaker 2: There are little things that you lose along the way.

Speaker 2: What sports I would be able to play later in life was pretty low on the list for me.

Speaker 2: At that point.

Speaker 2: I was asking myself questions like, am I still going to be employable?

Speaker 2: Can I have a job?

Speaker 2: That's probably something that, when you're going through a college experience, you ask yourself that all the time.

Speaker 2: Right.

Speaker 2: I was wondering, am I going to be able to meet a partner and have a family?

Speaker 2: Because that was really important to me.

Speaker 2: I was wondering things like, am I going to be able to sustain normal friendships?

Speaker 2: Can I still travel?

Speaker 2: What is on the menu of things that will be available to me in life?

Speaker 2: As I wake up to the reality that I'm legally blind, I've lost almost all of my vision.

Speaker 2: I'm going to have a little bit of vision left and thank goodness for that.

Speaker 2: But what does that mean for me?

Speaker 2: What can I still do?

Speaker 2: It took me a long time to process the list of things that might still be possible for me.

Speaker 2: And I didn't wake up to the fact that hockey might be possible for me until I put those skates on for the first time and tried skating, which was much later in life.

Speaker 1: So how did you actually come out of that stump when you were realizing what you cannot do and you were like, so this is for me, you know?

Speaker 2: Yeah, yeah.

Speaker 2: For anyone that's heard about the stages of grief, the final one is acceptance.

Speaker 2: Right.

Speaker 2: And I was in denial for a long time, not just about my vision loss, but about what my vision loss meant for the rest of my life.

Speaker 2: And I had to really work my way through the denial portion and the ways that I was coping with what I had lost vision wise, what I could still do, what was still possible, and sign myself up for a skating class, really as a way to break a lot of bad habits that I had in life, get myself out of the house and just put myself back out there and see if there was something in it for me.

Speaker 2: In ice skating.

Speaker 2: It was a way originally just to try and find some social connection, challenge myself a little bit physically and maybe use that as a tool to get involved in ice skating a little bit more.

Speaker 2: Because I thought, well, that's going to be hard enough.

Speaker 2: There's probably not any way I'm going to be able to play hockey.

Speaker 2: But I found out once I started ice skating that hockey might be a possibility for me.

Speaker 2: And that really opened up a lot of doors for mentally.

Speaker 1: So now looking at your book.

Speaker 1: So speaking of, like, sharing your story and your memoir, finding the Puck that just came out, what inspired you to write it?

Speaker 2: Let me give you a little background.

Speaker 2: I played for the U.S. national Blind Hockey team for a little while and have also played blind hockey all over North America pretty competitively, which is an unlikely story in and of itself, going from someone that had never even ice skated before to four years after that being in a training camp for Team usa.

Speaker 2: It's an unusual story.

Speaker 2: And when I tell that story, a lot of my friends that are in and around the game of hockey or who know about disability or both say, wow, you should really write that down some way.

Speaker 2: But the thing that really drove me to start writing stories like that down in earnest was I found out my wife was pregnant with our first kid in the spring of 2023.

Speaker 2: And having lost my own dad when I was only 10 years old, I didn't have much to remember him by when I was growing up.

Speaker 2: I had a few patches from his time in the Navy, but it's not like he was there for me to ask him about those experiences, right?

Speaker 2: So I started journaling at night.

Speaker 2: My wife, for some of the listeners that don't have kids or have never had a partner that's pregnant, this is what it's like.

Speaker 2: And if you want a family someday, this is what you're in for, right?

Speaker 2: If you're, if you're a woman and you're pregnant, you're going to be really tired, right?

Speaker 2: As soon as the sun goes down and you're going to go to bed in the first trimester, like around 7pm that was my wife's experience.

Speaker 2: She was in bed early every night.

Speaker 2: And then I'm looking around like, okay, well, we used to hang out all the time at night.

Speaker 2: And I, as the guy, okay, what do I do with all this time now?

Speaker 2: I obviously needed to worry more about.

Speaker 2: I cooked for her at night.

Speaker 2: I had to do things to support her.

Speaker 2: But when she's in bed, I had a couple hours every night where I could start journaling.

Speaker 2: So I started writing down stories to tell my son someday.

Speaker 2: He's almost two now.

Speaker 2: His name is Pace, and I started out just writing some stories for him.

Speaker 2: And then a friend of mine saw some of these stories and said, wow, you might have a book here.

Speaker 2: Have you thought about formatting these and turning them into a chronological order and then seeing if you can make a manuscript out of it?

Speaker 2: Pitch some literary agents, maybe go get a book deal, which is a long shot if you're just writing down some stories, right?

Speaker 2: So I, so I took that advice and worked with a developmental, a developmental editor that helped me turn some of these loosely affiliated stories into a coherent narrative and then pitched a bunch of literary agents to try and find representation.

Speaker 2: And I was lucky enough to find a wonderful literary agent named Marissa Corvisero who's been representing me for a couple years now.

Speaker 2: We got a book deal with a really well renowned sports publisher called Triumph Books, and they gave me a book deal.

Speaker 2: And fast forward to where we are today.

Speaker 2: The book is going to be out in less than two weeks from now.

Speaker 2: The publication date for the print book is January 27, and the audiobook is already live.

Speaker 2: So if you haven't already done so when you clicked on this episode, please press pause right now.

Speaker 2: I know a podcaster never wants anybody to say, please try pause.

Speaker 2: Press pause right now.

Speaker 2: If you're on your phone, go to Amazon, look up Finding the Puck, and please either buy the audiobook or the print version.

Speaker 2: All proceeds from both go to my foundation, which is called the International Blind Ice Hockey Foundation.

Speaker 2: And everything that we make off of this book is going to go toward helping provide equipment, training and ice time for blind athletes.

Speaker 1: So, guys, get the book from Amazon.

Speaker 1: Finding the Puck.

Speaker 1: And beyond playing and writing the book, you also run an International Blind Hockey feature, Ice Hockey Foundation.

Speaker 1: Right.

Speaker 1: So what's your vision for blind hockey over the next few years?

Speaker 2: Yeah, the International Blind Ice Hockey Foundation.

Speaker 2: Our mission is to knock down all of the barriers to ice hockey being a recognized sport in the Winter Paralympics.

Speaker 2: And for anybody that isn't super into sports, just bear with me because there's a lot of politics in here.

Speaker 2: Also, it's not just purely about the sports part.

Speaker 2: So you see, Olympics, the Olympics are coming up in a couple of weeks.

Speaker 2: The Winter Olympics.

Speaker 2: I hope everybody watches them.

Speaker 2: And hockey is usually one of the showcase events of the Winter Olympics every year.

Speaker 2: But then there's also this thing called the Paralympics.

Speaker 2: And believe it or not, there is no team sport for blind people in the Winter Paralympics.

Speaker 2: There are 45 million blind people globally and not a single Sport for those 45 million people to play in the Winter Paralympics.

Speaker 2: Not one.

Speaker 2: All of the blind sports are individual sports in the Winter Paralympics.

Speaker 2: So if you think about that as an access issue, if you think about it as a political issue, if you think about it just as an issue of this is a sport that's really worth people being able to watch, and for anybody that likes hockey, you would love watching it.

Speaker 2: You're right about all three of those things.

Speaker 2: This sport should be a Paralympic sport.

Speaker 2: Here's why it's not.

Speaker 2: In order to be a Paralympic sport, you need eight countries playing it competitively at the national team level.

Speaker 2: At the same time, you need to have had a couple of world championships and you need to have a competitive process for the countries that have a national team in that para sport to be able to qualify for the Paralympics.

Speaker 2: And not every country can make it.

Speaker 2: So right now, where we stand is the USA has a national team, Canada has a national team.

Speaker 2: Finland is very close to having a national team.

Speaker 2: And many of the players that will eventually be on their national team will be coming to compete in a tournament in Toronto this coming March.

Speaker 2: In just a couple of months from now, we're going to call that team World, and we're going to allow players from Finland, Sweden, maybe Mexico, if a couple of those players apply, maybe Asia, some of the different countries there, Germany, Czechia, any country where there might be blind skaters, we'll have a process to allow those players to play on something called Team World.

Speaker 2: And then eventually the players that play on that team will go back to their home countries, hopefully help start national programs.

Speaker 2: And then over the coming five, six years, the fundraising mission that we're on right now is to help many of those countries that I just mentioned, as well as potentially Japan, China, Sweden, maybe Slovakia, Russia.

Speaker 2: There are already players playing there.

Speaker 2: And again, there are a lot of reasons, and I'm not going to dive into them, why Russia's athletes are not allowed to be in the Winter Olympics this time, although many of the individuals are allowed to compete under no flag.

Speaker 2: So Russia will, once they're welcomed back into the fold politically, probably have a blind hockey team as well, and then you've maybe got your eight countries, and if we are able to get there within the next six or seven years, then there's a pretty good chance that when the Winter Olympics come to Salt Lake City in 2034, that our sport, blind hockey, will be on the ice in Salt Lake City.

Speaker 1: Yeah, hopefully, like in the few years.

Speaker 2: Hope so.

Speaker 1: Yes.

Speaker 2: There are a lot of people hoping so.

Speaker 1: And for many people, such as me, we've never seen or heard about blind hockey before it almost feels impossible to even imagine it.

Speaker 1: Could you describe what it's like on the ice?

Speaker 2: Yes.

Speaker 2: And if you're listening to this, I'm going to ask you, while I do this part, close your eyes.

Speaker 2: Now imagine that you're driving a car at around 20 miles an hour down the street with your eyes closed.

Speaker 2: And then you pull the steering wheel off of the column and chuck it out the window.

Speaker 2: That's the best, that's the best approximation that I can give to anyone that has never tried skating blind.

Speaker 2: To what it feels like to go that fast, to have this.

Speaker 2: You're riding like a razor's edge between recklessness and adventure and freedom and exhilaration.

Speaker 2: There are so many feelings that go through your mind when you're, when you're playing.

Speaker 2: But let me explain some of the mechanics of how we play blind hockey.

Speaker 2: So if you've never watched hockey before, then I'll try and talk about some of the basics.

Speaker 2: But assuming that you know a little bit about hockey.

Speaker 2: There are five skaters on each team and a goalie that's a total of 12 players on the ice at any one time.

Speaker 2: There are nets at either end of a 200 foot long rink that's got three different zones in it.

Speaker 2: There's the middle part of the ice, which is called the neutral zone, and two ends near the goals that are called the offensive and defensive zone, depending on which team you're on.

Speaker 2: And we've adapted ice hockey for the blind with three main changes from regulation hockey.

Speaker 2: The goal of the sport is to score more goals than your other team in a game.

Speaker 2: The first adaptation from regulation hockey is that we have a metal puck and I've actually got one here, so I'm going to rattle it.

Speaker 1: Oh, wow.

Speaker 2: That's what this puck sounds like when it's on the ice.

Speaker 2: And so for the players that play blind hockey, we all have to be legally blind.

Speaker 2: Worse, legally blind.

Speaker 2: For anyone that's not aware of the gradations of visual impairment, legally blind means your best corrected vision is 2200 or worse or you have less than 10% of your visual field left or both.

Speaker 2: In my case, I'm significantly worse than that.

Speaker 2: So I'm considered well past legally blind.

Speaker 2: But if your vision is worse than that line, then you're eligible to play blind hockey.

Speaker 2: Competitive.

Speaker 2: The skaters that skate on the ice in blind hockey, we all have a little bit of vision.

Speaker 2: Some of us almost none, some of us a little sliver like 5% of your vision, which is what I have.

Speaker 2: Some players have more than that.

Speaker 2: And so all of these legally blind players are skating around at almost 20 miles an hour trying to find this puck on the ice.

Speaker 2: That's part of why the title of the book is Finding the Puck, because that's one of the hardest things about blind hockey for us.

Speaker 2: So the puck is the first adaptation.

Speaker 2: The second adaptation is that if you've ever seen a hockey game, you may not know the exact dimensions of it, but a regulation net is 6ft wide by 4ft tall.

Speaker 2: And that's the net that all the players are trying to shoot the puck at or keep the puck out of, depending on which team you're on.

Speaker 2: A blind hockey net is 6ft wide by 3ft tall.

Speaker 2: The reason for that is the goalies in blind hockey have to be completely blind.

Speaker 2: Now, imagine that these.

Speaker 2: These people are badasses.

Speaker 2: Imagine being completely blindfolded, and like you're in front of a firing squad.

Speaker 2: You have, like, a cigarette in a blindfold, and somebody's about to start sending these metal cylinders at you at like, 70 miles an hour.

Speaker 2: It's pretty incredible.

Speaker 2: And if you ever get the chance to meet a blind hockey goalie, they're just as impressive of human beings as they are athletes.

Speaker 2: Every single one of them should have their own documentary made about them.

Speaker 2: My favorite goalie in blind hockey is this guy named Doug Goist, who is the starting goalie for Team USA and also a dear friend of mine.

Speaker 2: He lives in the Washington, D.C. area near me.

Speaker 2: And if you ever have a chance to listen to one of the interviews that Doug Goist has done about being a goalie, they're just incredible stories.

Speaker 2: So that's the second adaptation, is that the nets are a different size, and then the third one is to score a goal.

Speaker 2: In regulation hockey, any player can do it from anywhere on the ice.

Speaker 2: He can shoot the puck from all over.

Speaker 2: If you shoot it from farther away from the net, it's easier for the goalie to stop and the goalies can see.

Speaker 2: But in blind hockey, because everybody is using either very little or no vision to try and track this puck, you have to complete a pass to your teammate inside of the offensive zone, which is inside of this thing called the blue line that's within about 50ft or so of the net before you can actually score a goal.

Speaker 2: And then the referee, once that pass has been completed, will blow this thing called a pass whistle.

Speaker 2: And it sounds like this.

Speaker 2: Like a high, shrill whistle for a few seconds that lets everybody in the ice know that the puck is now eligible to be shot at the net, and the attacking team can score.

Speaker 2: And other than that, it's played at probably 90% of the speed of the hockey games that you've seen on television.

Speaker 2: It's a very impressive sport to watch.

Speaker 2: And if you've never had the chance to see a blind hockey game, go on YouTube as soon as you're done listening to this and look up the blind hockey league.

Speaker 2: I'm actually a player in the blind hockey league, BHL for short.

Speaker 2: That's our professional version of blind hockey, where the best players from the US Team Canada, as well as the rest of the world come together and compete at the peak of our sport.

Speaker 2: And if you watch a blind hockey league game, you will be, I think, very impressed by what the athletes in blind hockey are able to accomplish.

Speaker 1: So also, when you're on ice, do the team players communicate a lot?

Speaker 2: Tons, yeah.

Speaker 1: Is there a lot of communication?

Speaker 2: Yes.

Speaker 2: And just imagine you just took me to the water fountain right before we started recording here, and you were communicating with me.

Speaker 2: The door's a little bit ahead.

Speaker 2: Turn right, not left.

Speaker 2: Okay.

Speaker 2: It's over here.

Speaker 1: Yes.

Speaker 2: Over here is usually less good on the ice than right or left or 10ft or.

Speaker 2: Or.

Speaker 2: My team has it.

Speaker 2: You know, black team has it.

Speaker 2: Yeah.

Speaker 2: So it's very specific, very crisp communication that's directional and very intentional about what you want your other teammates to do.

Speaker 2: And we have our own special kinds of communication.

Speaker 2: So the goalie in blind hockey will be tracking the puck and saying, puck left, puck, right, puck, middle.

Speaker 2: The defenseman will be talking to the goalie, and if they can see a little bit, telling the goalie what they think is about to happen, who has the puck, who's near the net?

Speaker 2: And then the forwards will all be talking to each other and kind of directing traffic, because the forwards usually have a little bit more vision than the defensemen do.

Speaker 2: So a forward, when your team gains possession of the puck, will often be telling other people where to go.

Speaker 2: But I always like to tell people that ask me this question, that blind hockey players probably communicate about double the amount that regulation hockey players do on the ice just because we have to.

Speaker 2: And if you ever go see a blind hockey game live, we ask that you not cheer during the game so that those of us that are on the ice can hear the puck moving around and also hear each other.

Speaker 2: But there is almost constant communication on both the benches and on the ice during a blind hockey game.

Speaker 1: Okay.

Speaker 1: And I got to know that you went to the NHL for blind hockey on tnt.

Speaker 1: So that must have been surreal.

Speaker 1: So what was that experience like for you?

Speaker 2: Oh, wow.

Speaker 2: Well, I'm grateful for every chance that I get to talk about blind hockey.

Speaker 2: You know, I'm toward the end of my blind hockey career myself, and I'm really shifting my thinking toward what can I help build for that next generation of players that's coming behind me.

Speaker 2: So when I get asked to go talk about blind hockey, especially when I get asked to go talk about blind hockey and bring a puck and get a chance to teach Wayne Gretzky about blind hockey, that was obviously a once in a lifetime surreal moment.

Speaker 2: And really what it was for me was, I don't know that I was the perfect blind hockey player to be invited into that setting.

Speaker 2: I'm not the best blind hockey player in the United States, let alone the world.

Speaker 2: I'm probably not even one of the 10 best in the United States anymore.

Speaker 2: But I really was excited to be asked to be a messenger and an ambassador for our game and talk about why it's important that blind people be given the chance to play blind hockey.

Speaker 2: Our sport is really probably 80% about what happens for the athletes who play it off the ice and 20% about what happens on the ice.

Speaker 2: And being given the opportunity to be on a platform as significant as TNT's national broadcast for an NHL game and tell that story to an audience that massive was.

Speaker 2: It was a great experience for me.

Speaker 2: But I think the more important thing about it is it was a great chance to allow our sport to be seen by hockey fans that had never heard of it before.

Speaker 2: And I was really excited about the feedback that we got after I was invited after the TNT appearance to also be on the most watched hockey podcast, which is called Spit and Chiclets.

Speaker 2: And that was a surreal experience.

Speaker 2: And even being here is.

Speaker 2: It's an incredible chance every chance I get to tell people that have never heard of it about blind hockey.

Speaker 2: So blind athletes need your help.

Speaker 2: We.

Speaker 2: It's not just acknowledgement like, wow, that's really cool.

Speaker 2: So if you're listening to this and you're wondering, how can I help?

Speaker 2: Well, if you're visually impaired, get in touch with us at www.supportblindhockey.org.

Speaker 2: if you'd like to know more about participating in blind hockey or being connected with the blind hockey community.

Speaker 2: And for anybody that isn't visually impaired but wants to know how you can help, please visit us there as well.

Speaker 2: It's www.supportblindhockey.org and.

Speaker 2: And go watch some of.

Speaker 2: Watch some of these games.

Speaker 2: Watch the appearances on TNT and on Spit and Chiclets, you know, after you've listened to this episode.

Speaker 2: But just to put a bow on the answer to the question that you just asked, being able to get onto a platform like that and be a spokesperson for blind hockey's message really helped a lot of people.

Speaker 2: And I'm really grateful for the chance to open up doors for as many.

Speaker 1: People as we did and to end the interview.

Speaker 1: So for someone listening who might be losing their vision but still wants to chase their passion, what advice would you give them?

Speaker 2: Yeah, be a good teammate.

Speaker 2: So here's what I mean by that.

Speaker 2: Being blind is a team sport.

Speaker 2: And when you start losing your vision, it's just so incredibly isolating.

Speaker 2: Not just socially and emotionally, but physically and literally.

Speaker 2: The world starts closing in around you.

Speaker 2: You can't see what's happening anymore.

Speaker 2: You don't know if somebody is near you.

Speaker 2: You don't know if that might be your mom waiting for you outside security at the airport waiting to give you a hug.

Speaker 2: You start feeling disconnected from what's going on around you.

Speaker 2: But the way that you overcome that is to think about the people that are around you as your teammates.

Speaker 2: And that means two main things.

Speaker 2: First of all, accept the help that people offer you with gratitude.

Speaker 2: Don't be too proud.

Speaker 2: Don't be this person who isolates yourself and thinks, okay, I don't need help crossing the street.

Speaker 2: I don't need a ride to go to the grocery store.

Speaker 2: Accept the help with gratitude and with grace and with humility.

Speaker 2: And realize that there are going to be things that you're going to need help with the rest of your life.

Speaker 2: The sooner you get over that mental hurdle and accept that, the sooner you can actually start finding some joy again.

Speaker 2: But the flip side of that is just as important.

Speaker 2: And this is why I say, be a good teammate with the same gratitude and humility that you accept help.

Speaker 2: Seek out opportunities to help other people and lift them up, too.

Speaker 2: Whether that's something little, like for me with my wife.

Speaker 2: My wife is the best teammate I know.

Speaker 2: She does so many things that I can't do for myself without me even having to ask.

Speaker 2: That means that I have to double or even triple my efforts to do things for her without her having to ask.

Speaker 2: Also, we've got a son that's nearly two.

Speaker 2: There are a lot of things that he needs in terms of care for him.

Speaker 2: Step up and just get it done.

Speaker 2: And don't even have a conversation about it.

Speaker 2: I get up an hour before my wife every morning and I go downstairs and make her favorite matcha latte and have a cooked breakfast waiting for her and empty the dishwasher and take care of the dogs and whatever else is needed that morning.

Speaker 2: Just as a little way to show her that I love her, that I appreciate her, but just as importantly, I want to be a good teammate to her.

Speaker 2: So.

Speaker 2: And this doesn't just apply to blindness.

Speaker 2: If you're losing the ability to do something in life or you find yourself kind of, you know, needing a hand, accept the help with humility and grace.

Speaker 2: But challenge yourself to be a good teammate back to the people that help you.

Speaker 2: Do as much for them as they do for you.

Speaker 2: And then you'll find that you get confidence back, you get self esteem back.

Speaker 2: You find out what you still can do and you realize that you're just as valuable to your teammates as they are to you.

Speaker 1: Thank you.

Speaker 1: That was wonderful.

Speaker 1: This has been Eye on the triangle from WKNC 88.1 FM HD1 rally.

Speaker 1: Our theme song is Krakatoa by Noah Stark, licensed under Creative Commons.

Speaker 1: To re listen to this or any other episode, visit wknc.org podcast or subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

Speaker 1: Thank you for listening.